THIS BLOG IS MY ATTEMPT TO PRESENT IN LOGICAL ORDER MY CONTRIBUTIONS TO A TAROT HISTORY FORUM THREAD AT http://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=12&t=463, WITH REVISIONS DONE IN JUNE OF 2012 AND PARAPHRASES OF THE OTHER MAIN PARTICIPANT'S OBJECTIONS. ON PARTICULAR POINTS, THERE MAY BE FULLER DISCUSSION IN THE THREAD ITSELF.

THIS BLOG IS ARRANGED LIKE A BOOK, GOING DOWN THE PAGE FROM THE TOP DOWN AND FROM "NEWER POST" TO "OLDER POST."

My hypothesis, for which I am going to try to provide evidence, is that the so-called "tarocchi of Mantegna" started with three of the "Belfiore Muses" of c. 1449 Ferrara, which was expanded into more in the same style, more probably Bologna than Ferrara, starring as early as the 1450s, and then converted to the new technology of engraving by 1467, probably there as well.

Actually, it is not my idea, but my version, incorporating the new research, of an old idea once advocated by Venturi (1931) and included by Hind (1938) in his survey of the options.. I will present their views in relation to both the current art historians, who have declared for 1460's Ferrara, and Trionfi, which prefers c. 1474-1475 for the complete set of designs and Rome for the engravings. At the risk of giving you too much information, Details of abbreviated references are at the end.

HIND'S VIEWS ABOUT THE DESIGNER OF THE "MANTEGNA"

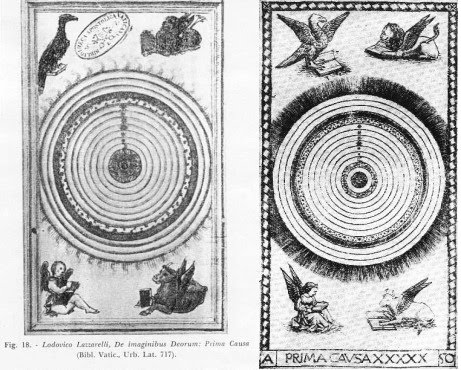

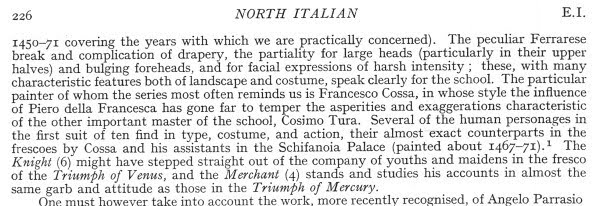

These scans are taken from a book that is not easily accessible, Arthur M. Hind's Early Italian Engravings. The copy to which I have access, in a nearby college library, says it is one of 375 copies signed by Hind.. So to be sure that we are getting him correctly, untilfiltered through my imperfect editing of him, I will post scans of the relevant sections, He begins by saying that the style is Ferrarese, and asking, could any of known artists of Ferrara have designed the cards? He starts with del Cossa. Here is his the beginning of his text:

It has been known since 1885 that del Cossa only claimed credit for March, April, and May. The Triumph of Venus is the upper part of April, and Mercury that of June. Different historians have seen resemblances to the cards in nearly every section of the Schifanoia. I will post side by side comparisons later..

Next Hind considers Gombosi's and Clark's idea of Angelo Parrasio, the painter that Leonello put in charge of the Belfiore Muse project. Here is what Hind says:

Notice here that Hind picks out three of the Belfiore Muses. I will start my own investigation with them. But Angelo could not have designed the engravings, Hind reasons, because he died in 1456, and "it seems difficult, on technical grounds, to place the engravings before 1460, and I think 'about 1465' a more probable date." Few historians today identify the artist of any of the three as Angelo; instead they say "anonymous Ferrarese," as we shall see. Whichever artist it was, Hind says, "this group of painters [i.e. the Belfiore artists] exercised considerable influence" on "our engraver." Hind talks about two persons being involved:. one is the artist, the other a technician who renders the artist's work in copper. Hence a design, it seems to me, could outlive its designer and be rendered in a technically later engraving.

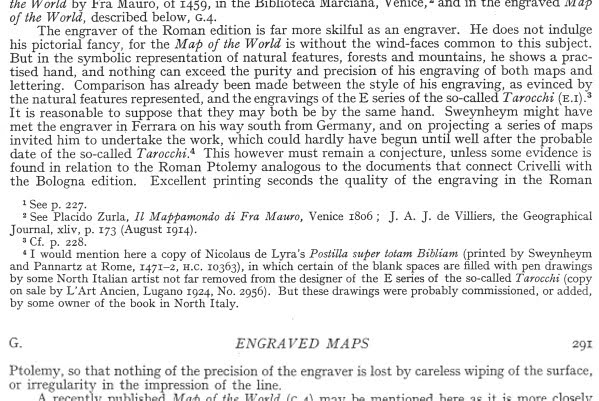

Not seeing any candidates among the master-painters, Hind turns to the miniaturists and] the designers of cards and other decorative items. Although he thinks the miniaturists are more probable as designers of the "Mantegna" than the painters of larger works, he finds the style of those in Ferrara more like the "true tarocchi" than the Mantegna Of the card-makers,:he thinks they are the most likely to have designed the "Mantegna." In the selection below, I go to the end of Hind's discussion, in which he not only discusses the designer but makes his by-now famous suggestion as to the engraver. Start on the fifth line below.

The next to last paragraph here Is quoted by Trionfi in their section "Hind's final suggestion" at http://trionfi.com/0/m/00/. We shall see that it is not Hind's "final suggestion." I will quote more of Hind, from his section G.2 to which he refers, in a later discussion, when I come to the question of the engraver.

THE BELFIORE MUSES

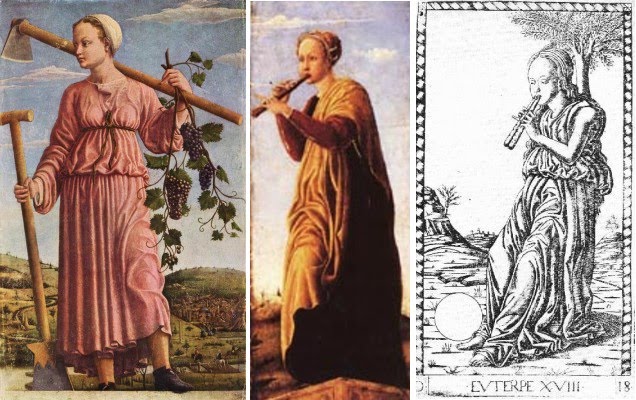

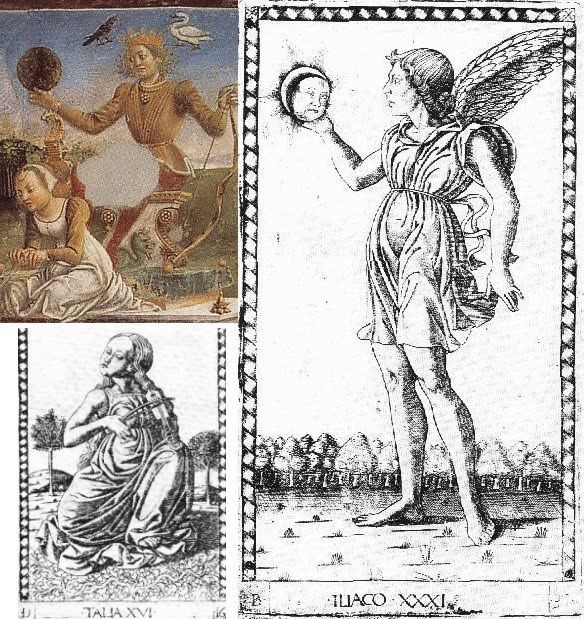

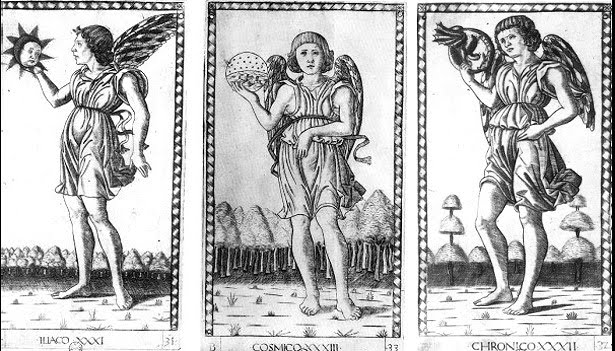

The first question I will address is this: in the style of what artist are the designs? To focus this question, here are two paintings done c. 1450 in Ferrara (two of the three that Hind singled out for attention; you can see the third at the beginning of the next section. With these two, I give the E series engraving of the "Mantegna's" Euterpe, one of the nine "Mantegna" Muses. It would appear that the top half of one painting and the bottom half of the other combine to make one "Mantegna" Euterpe.

Art historians today agree, on good evidence, that the left-hand painting, now identified as the Muse Polyhymnia, was done for Leonello d'Este's studiola in his new Belfiore Palace, c. 1450. The other, Euterpe, is not much mentioned, but when it is (Gombosi, De Romanis), it is usually located at the same place. The palace and studiola were destroyed in one of Ferrara's disastrous earthquakes, probably that of 1593; but likely eight of the paintings are still extant, in various museums, with various histories, and in various styles. (A convenient website to see seven of them, lacking only the one on the left above, and with a good summary, is Allesandra De Romanis's http://www.italica.rai.it/rinascimento/parole_chiave/schede/belfiore.htm; I get it from a post of Marco's on another thread.) In several cases, as x-ray studies have confirmed, paintings in one style were painted over, partly or wholly, and redone in a different style. The repainting is in the style of Cosmé Tura, and so by him and perhaps an assistant in the late 1450's, probably at the request of Borso d'Este, who succeeded Leonello as Marquis of Ferrara.

Four of the Muse paintings received only minor retouching. One, sometimes identified as Thalia, was done by Michele Pannonio, signed by him, and in a different style than any of the others; it does not concern us here. The others are the two above and one more in the same style, shown below. These three are the only ones that have their Muses standing rather than sitting. For both reasons, some historians (Baxandall, Eorsi, Boskovits, all cited on p. 169 of Campbell 1997) have theorized that they were done for a different series of Muses. However the wood on the left-hand painting above is from the same log as three other Belfiore Muses, and it has the same type of white undercoating, done before the modifications (Dunkerton, pp. 108, 109, 114)

The paintings loosely follow a program for them written by Guarino da Verona, Leonello's old tutor (Campbell 1997, p. 31, with the Latin original on p. 169). The Malatesta Chapel in Rimini followed his program more precisely. A quotation from the program actually appears on one of the other Belfiore Muse paintings. In Guarino's program, Euterpe was Muse of the pipes, and Polyhymnia, Muse of crop cultivation. The Euterpe appears to have been had part of its left side removed, as it is narrower than most of the others, although exactly the same length. Probably the same is true of the third one, identified as Melpomene, having the same dimensions.

What happened to the three after the Belfiore? According to 19th-early 20th century art historian Adolfo Venturi (p. 29), the two narrow ones served as side-panels in a Bologna church, as "angel-musicians," in Venturi's phrase, and then resided in the collection of Marquis Nerio Malvezzi of that city. They are both now in the Fine Arts Museum of Budapest. The Polyhymnia has been in Berlin since at least the 19th century.

THE ARTIST

So who painted these three? The antiquarian merchant and traveler Ciriaco da Ancona, who visited Belfiore on July 13, 1449, said that of the 9 paintings commissioned, 2 were completed, Clio and Melpomene; he names the artist as Angelo Parrasio. Here is his description of Clio:

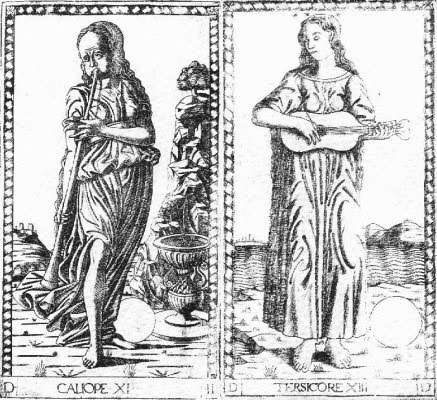

This painting, although its description reminds me of a certain Vermeer (http://www.essentialvermeer.com/catalogue_xl/xl_art_of_painting.html), seems to have been lost. The "Mantegna's" Clio (at left, below) has something of the same mood, but with different accoutrements.The former, conspicuous for her dress embroidered in purple and gold, and for her blue chlamys, holds in her right hand a trumpet, in her left an open book, and with a certain modest hilarity in her expressive face, and something of a glance of her eyes, seems to urge men on to glory (Venturi p. 28f).

And here is Ciriaco's description of the Melpomene:

He also mentions flowers at Melpomene's feet, painted so realistically that they deceived the bees (he is repeating a standard phrase, probably deriving from a classical source such as Philostratus). The Budapest Melpomene painting (center above) seems to have the same robe and harp.Her shoulders covered by a purple robe, she lightly touches the strings of her harp, turns her rapt gaze towards Olympus, and with modest and grave enthusiasm tunes her songs to the harmony of her chords.

Oddly, Venturi did not identify this description of a Muse with the painting at all, but simply called it an "angel musician." Perhaps he considered it too great a departure from Ciriaco's description, because of the improbability of flowers, and because she does not appear to touch the strings. But these are fine points; Ciriaco was a merchant, a promoter of goods, albeit one who had been to Egypt and knew his antiquities. To her right above, I put the "Mantegna" Melpomene. Obviously we do not have a match. The engravings are the product of a different environment, either with a different patron or one who changed his mind. But the style is similar. I will elaborate further on this point later.

The painter, whom Ciriaco called Angelo Parrasio, is also known as Angelo Maccagnino; he came to Ferrara from Siena in 1447, and Leonello put him in charge of the Muses project. Georg Gombosi, writing in 1933, attributed the Euterpe and the Melpemone to him. More recently Jill Dunkerton (2002, p. 114) attributed the Polyhymnia to him as well. But most scholars today disagree: none of the three is in Angelo's style. Dying in 1456, he was already old in 1450, and painted in an older style, visible e.g. in the upper body of the Erato, while the others reflect a new style, like that of Piero della Francesco. Campbell attributes the Polyhymnia to "an anonymous artist influenced by Piero della Francesca (in Ferrara around 1450)" (1997, p. 33). In the caption to the painting he says "Ferrarese, c. 1450" (p. 35). He does not discuss the others, but De Romanis, in her web essay on the Muse paintings already cited, attributes all three to "anonymous Ferrarese" ("anonimo artista ferrarese" and "ugualmente di anonimo ferrarese"). Nicoletta Guidibaldi, in Prospettive di Iconografia Muisicale (in Google Books) uses the same words.

Adolpho Venturi claimed that the painter of all three was one Galasso Galassi (p. 30), also called Galasso di Matteo Piva (p. 24), whom he also held, because of stylistic similarity, was the originator of the "Mantegna" designs. Venturi's opinion was reaffirmed in 1954 by Gnudi, and earlier by Longhi according to Gnudi, in a critical notice excerpted by Trionfi (in the section "Artists active in the Studiola," http://trionfi.com/0/m/16/).

Gombosi, in his 1933 Burlington Magazine article (at http://trionfi.com/0/m/16/) took issue with Venturi. He attributed the Polyhymnia to Galasso but the other two to Angelo, despite the lack of similarity in overall composition and mood to the other Angelo Muses, the ones altered by Tura. (At http://www.italica.rai.it/rinascimento/parole_chiave/schede/belfiore.htm, compare Euterpe and Melpemone to Erato, Terpsichore, and Urania.) Gombosi based his attribution to Angelo on similarities to the other Angelo Muses in the depiction of folds in fabric, and on his identification of the landscape as Umbrian. However x-ray analysis since has revealed that the folds were put there later in the repainting (Dunkerton p. 116f); as for the landscape, it seems to me rather generic, easily learned from others' example. Gombosi noted the similarity in style of the Euterpe and Melpemone to the "Mantegna," to this extent following Venturi, and identified the cards as "Ferrarese (or Bolognese, but hardly Venetian)."

Galasso's name appears in one contemporary document, showing payment to Cosmé Tura and Galasso for appraising the value of some pennants done for the d'Este court in June 1451 (Venturi p. 29, Tyson p. 35). Tura was the artist in charge of painting over, in his style, all or part of some of the original paintings, all seated Muses: the unfinished Calliope completely, and three others, Erato, Urania, and Terpsichore partially (Dunkerton, pp. 108, 109, 114). So he and Galasso were in 1450 likely both students of Angelo, with similar ways of painting folds in fabric. But the three standing Muses are not in Tura's style. It is theoretically possible that he painted some of the originals in an early style and then painted over them later in a different style. But there is no documentation of Tura paintings suggesting that style.

Galasso's name next turns up in Vasari (Vol. 2, 1st edition only), who says that he was trained in Ferrara and then moved to Bologna at the invitation of "some Dominican monks" (p. 126), where he died at about age 50. According to Vasari's 1871 English translator, he lived 1438-1488. Venturi says he died in 1470 and that he worked for Bessarion, the papal legate in Bologna 1450-1455. Vasari's translator mentions another account of his life in a nineteenth century Italian source, which I have not consulted.

I have found only one recent art historian mentioning Galasso. Drogin, writing in 2002 of Bologna during the time of the Bentivoglio, says, "Piero della Francesca perhaps visited around 1450, followed by his student Galasso, to whom a 1455 Funeral of the Virgin is attributed (San Michele in Monte, destroyed 1831" (p. 80). Drogin does not give a reference.

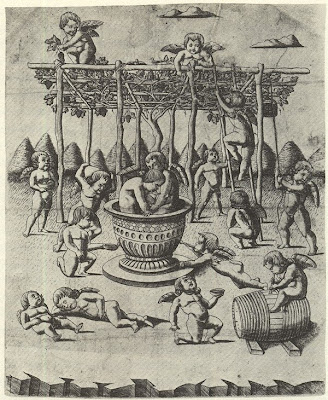

I have been focusing on just one of the 50 images in the "Mantegna." But all are in a similar style, if not in the same hand. (Lambert, p. 145, suggests a workshop, an "atelier." Lambert is conservator in the Departement des Estampes et de la Photographie at the Bibliotheque Nationale, and her book is a catalogue of that library’s holdings.) The Muses, Virtues, and Liberal Arts are especially similar, mostly standing figures in robes. Before the "Mantegna" images this style was not a common one: I have seen nothing quite like them, apart from the three standing Muses of Belfiore.

It is not unthinkable that Galasso took drawings of his three Muses with him to Bologna and with the help of humanists there, perhaps Bessarion himself, redid them and added more. One such humanist is a name that Trionfi mentions in their section, "Mantegna Tarocchi Engravers," for his interest in printers: Niccolo Perrati, Poet Laureate of Bologna in 1452 (the time of Frederick III's marriage journey), sometime secretary to Bessarion.

I wish to emphasize that the designs of all the figures need not have been Gelasso. Numerous artists, including miniaturists, came to Bologna during Bessarion's tenure as prelate and after.

In this new environment, with new designs, it is the style that continues, not the programmatic details. Admittedly, no professional art historian today makes Venturi's leap to Galasso and Bologna. Stephen Campbell says that the "Mantegna" was "devised by a Ferrarese artist and circulating by the 1460's" (2004, p. 127). Tyson agrees (p. 57), suggesting a candidate for the designer, Gherardo da Vicenza, the triumph-card maker, because his dates are right, because documents show that he designed other things for the Estensi, such as silverware, and because there are possible affinities between the cards and anonymous sections of the Schifanoia frescoes. To me that is not much of an argument for Gherardo in particular.The d'Este cards of c. 1473, to which he would be expected to have made some contribution, don't look a bit like the "Mantegna."

Hind, in his 1938 discusssion of the "Mantegna (p. 228),, mentioned several other painters of playing cards at the Ferrara court in the 1460s, besides Gherardo, who could have done the job:

Among painters specifically of playing cards at the same court are named Allesandro di Bartolommeo Quartesano, Don Domenico Messore, Giovanni di Lazaro, Cagnola, and an amateur named Petrecino of Florence, a paage of the Duke. But even if the designer of the engravings is to be found among such names, there is no clue to help us to fix on any one of them.One reason that Campbell gives the 1460's rather than earlier, is his theory (2004, p. 126f) that several literary and artistic productions of that time, including the "Mantegna" and the Lazarelli poem, were reacting to the seductive, morally ambiguous nature of the Belfiore Muses, as they were in the late 1450's; they wished to present the Muses in a more elevated way. Whatever the merits of this argument, it applies only to the Tura repaintings, and not to the three unaltered ones. As far as a reaction against Tura's and del Cossa's style, the Schifanoia at least, 1469-71, in its most conspicuosu parts, the so-called "decan images", shows no such restraint. it seems to me that eople were capable of appreciating both styles, whether at the time of the Belfiore Muses or later.

In the captions to their reproductions of the cards, the art historians say "anonymous Ferrarese," meaning "anonymous painter from Ferrara," as opposed to "painter in Ferrara." This curiously not ruling out the possibility. Galasso was always a Ferrarese--as were many other painters who came to Bologna from Ferrara at one time or another..

THE ENGRAVINGS: A 1467 MANUSCRIPT IN BOLOGNA

I turn now to the engravings. Most painters did not have engraving skills. Engraving started in Germany in the 1430’s, per Wikipedia, but both Ferrara and Bologna had active engraving and printing communities in the 1450's and later, including, at least in Bologna, German shops. Lambert (p. 146) classifies the "Mantegna" as "burin proche de la maniere fine Florentine," which I translate as "burin close to the fine Florentine manner." "Burin" in English means the engraving tool; perhaps in French it means "engraving" as well. Indeed, the "Mantegna" engravings are technically similar to Florentine ones of the 1460's reproduced by Lambert. Others that she attributes to Ferrara and elsewhere she calls simply "burin," except for Florentine ones, which she calls "burin en maniere fine." (Looking at the reproductions, I can't see any difference among them.) At that time, the 1450's and 1460's, Florence was closely allied politically with Bologna, Bologna's leading citizen having grown up in Tuscany and Florence; but Ferrara was considered an enemy. Numerous Florentine craftsmen came to Bologna to build and decorate the palaces of the rich, a trend in which the leading family set a strong example (Ady, p. 150ff).

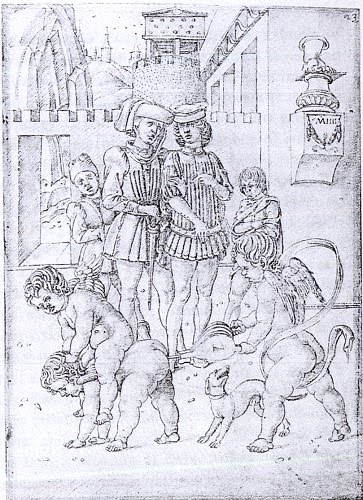

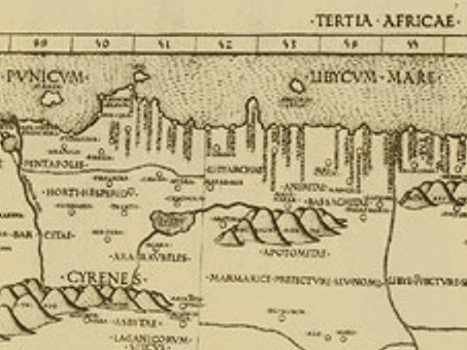

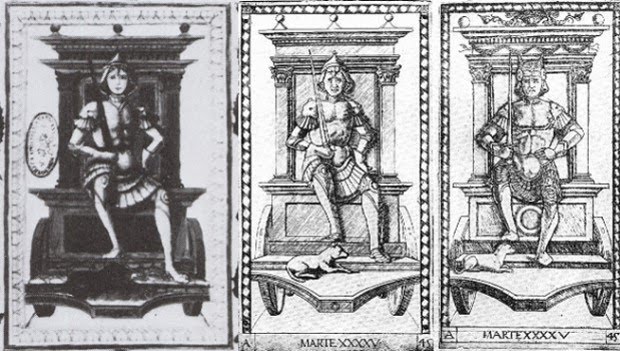

We do know that the next appearance of something similar to the "Mantegna's" imagery was in Bologna, in a 1467 miniature, of an Emperor and a Pope (Lambert p. 145 etc.). The miniature is posted by Trionfi at http://trionfi.com/i/mantegna-tarocchi/index2.php. I post the relevant section below, underneath three “Mantegna” cards. Trionfi observes, in their comments below the photo, that besides the Emperor and Pope is also a figure similar to the "Mantegna" Servant, "Il Fameio." I assume they mean the person at the far left of the Pope. So above the miniature, I put all three cards for comparison. The figure of the Servant is possibly repeated to the Pope's right; but the face and costume resembles more the Merchant. I also see the Chevalier behind and to the left of the Emperor, possibly repeated on his right. And there is a bearded version of the "Mantegna" King kneeling before the Emperor. I post these three below the miniature, for ease in making visual comparisons.

Possibly the four minor characters are stock figures of a generic nature. Lambert does not list them. The Emperor in the miniature is indisputably a close match with the "Mantegna" Emperor (and also the figure in its “Jupiter”: see http://trionfi.com/mantegna/e/e-mantegna-tarocchi/46.jpg). With the Pope there are some similarities, such as the tiara and the keys, but also some differences. His posture is different. The robe is more elaborate, filled with abstract designs. The face is different, too. So is the miniaturist's version a a more complex version of the card, but with a rounder face, or is the cardmaker's a simplification of the miniature, with a thinner face?

The posture can be explained by reference to the other side of the illustration, with the Emperor: the two figures are meant to complement each other. This explanation, while accounting for the difference, does not answer our question of which came first. The face and robe, I think, demand a more complex explanation, but one that may yield more interesting results.

We must first look at the "Mantegna" Pope card in the context of 15th century Popes. One of Trionfi's arguments for the engravings' late date, c. 1475, is a resemblance that they perceive between the "Mantegna" Pope and Sixtus IV, who became Pope in 1471 (http://trionfi.com/0/m/05/).

Admittedly, the man on the card is not similar to his predecessor, 1464-1474, Paul II, who reigned while relatively young and portly (for his portrait, scroll down about 4 images). But I am arguing that the cards started being designed in the 1450's, in the form of drawings; so we should also compare the card to the Popes then. There is also the element of the keys in the "Mantegna" Pope's hand. Nicholas V (1447-1455), the Pope who appointed Bessarion papal legate and let the Bolognese largely run their own affairs (Ady, p. 37), had just such keys as his personal device, frequently added in the corner of his portrait. Here is an example:

To me the Pope card looks like him. And if not Nicholas V, there were two after him in the 1450's; even without the device, keys were associated with Popes. I cannot see how the Pope card looks more like Sixtus IV than any of these. Below are Callistus II (1455-1458) and Pius II (1458-1464), (http://catholicsites.org/popes/renaissance.html), with the "Mantegna" in the middle.

As I say, to me there is a good match to Nicholas V, the one I showed first, for whom the keys were a personal device, who reigned 1447-1455 and was much beloved by humanists for his sponsorship of the translation of Greek texts into Latin.

.

Now the strange result--well, not so strange--is that the Pope in the miniature does not look like any of the above, but rather like Paul II, the Pope from 1464 to 1471, whose likeness we see on the right below: (After writing this I found that Zucker, in The Illustrated Bartsch, Vol 24 Part 3, footnote p. 7, makes this same association. Also, he associates the Emperor to Theodosius.)

So we can date the miniature to that period as indeed it is, 1467. But the card, based on this evidence, is likely either before or after that period. I of course think it was before. But at least we have an explanation of why the face is different.

As for the robe, it may be that Paul II wore such things. The portrait posted on Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pope_Paul_II) shows a golden robe with intricate designs. He was 47 when elected Pope and so may have lacked the austerity that often comes with age. He had been a merchant before changing careers when his uncle was elected Pope (in the end advancing from a lower “Condition of Life” to the highest.) And the late 1460's was a time for magnificence: Florence's Medici, Milan's Sforza, Bologna's Bentivoglio, Ferrara's Este, etc. Such a robe also gave the miniaturist a place to show off his skill. Moreover, the patterns themselves have an interesting characteristic, at the top and bottom of the double key that the Pope is holding in his right hand: the patterns merge with the key edges, so that someone might not recognize the key at first. It is a kind of visual double entendre, another way in which the miniaturist shows off his skill. For the pun and its reference to be appreciated, however, people would likely have to have been familiar with the card; Nicholas V and other popes were not shown actually holding the keys in the manner depicted.

So tentatively we can say that the manuscript came after the card, or at least the image on the card, i.e. before 1467.

REFERENCES NOT DETAILED IN POST OR LINKS

Ady, Cecilia, 1937. The Bentivoglios of Bologna.

Campbell, Stephen J., 1997. Cosmé Tura of Ferrara.

Campbell, Stephen J., 2004. The Cabinet of Eros: Renaissance Mythological Painting and the Studiola of Isabella d'Este. In Google Books.

Drogin, David, 2002. "Bologna's Bentivoglio Family and its Artists: Overview of a Quattrocento Court in the Making, in Artists at Court: Image-Making and Identity, 1300-1550, 2002, ed. Stephen Campbell, pp. 72-90.

Dunkerton, Jill, 2002. "Cosmé Tura's Painting technique," in Cosmé Ture: Painting and Design in Renaissance Ferrara, ed. Alan Chong, pp. 107-152.

Giovannoni, Giannino, 1981. Mantova e i tarocchi del Mantegna.

Lambert, Gisele, 1999. Les Premieres Gravures Italiennes: Quattrocento--Debut du Cinquecento.

Levenson, Oberhuber, and Sheehan 1973. Early Italian Engravings from the National Gallery of Art.

Seznec, Jean, trans. 1953. Survival of the Pagan Gods: The Mythological tradition and its Place in Renaissance Humanism and Art, trans. Sessions.

Skelton,

Syson, Luke, 2002. "Tura and the 'Minor Arts': The School of Ferrara," in Cosme Turé: Painting and Design in Renaissance Ferrara, ed. Alan Chong, pp. 31-70.

Vasari, Giorgio, 1871 translation of 1550 original. Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Vol. 2, translator Johnson, in Google Books.

Venturi, Adolfo, 1931. North Italian painting of the Quattrocento: Emilia.

Next, the Gentleman, both selections from April.

Next, the Gentleman, both selections from April.

I

also see Thalia on the April wall, sitting on the ground, while above

her Euterpe and Terpshicore are standing, holding their instruments:

I

also see Thalia on the April wall, sitting on the ground, while above

her Euterpe and Terpshicore are standing, holding their instruments:

On Saturn, Lazarelli specifies just the merest sign of a beard.

On Saturn, Lazarelli specifies just the merest sign of a beard.