It is extremely difficult to track down the identity of the engraver. 75 years after Hind, the issue remains unresolved. We have to consider not only engravers of mythological scenes but also of maps, since lettering is involved and Hind noticed a similarity with the 1478 Ptolemy.

Zucker and Levenson et al (p. 88)have given us two engravings that they identify as by the same engraver. One is that of some putti in a vineyard. Here it is again.

These trees were one of the features that led Hind to identify the "Mantegna's" engraver with that of the 1478 Ptolemy. But who is he? The National Gallery authors reproduce a drawing that is like the engraving but without the trees (p. 88, not posted here; it is in the Gabinatto Nazionale delle Stampe, Rome). For the trees themselves, I see similar ones in Gozoli's Procession of the Magi.

Another factor is the resemblance of the scene to certain Roman sarcophagi. An example is this one at the Getty Villa in Malibu (http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/art ... obj=311978).

The Getty does not say where this sarcophagus was in the 15th century. But I know that Mantegna's "Bacchanal" engravings were inspired by a Bacchic procession sarcophagus in the villa of Lorenzo dei Medici (Lambert p. 193f). "Bacchic frenzies" was a theme dear to his Academy and expressed poetically by Poliziano (Hind p. 76). Perhaps Lorenzo also had a grape-harvest sarcophagus. Alternatively, it could have been in Rome, where Hind (p. 75) says a couple of other grape-themed sarcophagi were from, these inspiring a later Florentine engraving of Maenads with grapes.

Another place that has similar trees, but not as similar as the ones with the putti, is in the Florentine Baldini's "Planets," 1460-1465. Examples are in his "Sol."

These examples are both Florentine.

Anodd thing about the engraving of the putti in the vinyard is the middle-aged faces on some of the puttis' bodies. Looking in several books of early Italian engravings, I have found only one engraving with similar putti: Plate 35 of Donati's 1944 Incisioni Fiorentine del Quattrocento. It is another on the same theme, cupids and grapes, this one housed in the Ufizzi. Donati called it Florentine, c. 1470.

In painting, I find no similar putti except in miniatures. The National Gallery authors, as much as Hind, see the Ferrarese miniaturists as possible candidates for engraver of the "Mantegna." In The Painted Page, I found only three miniaturists with similarly odd-looking putti.

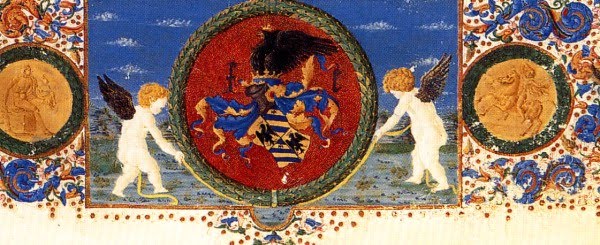

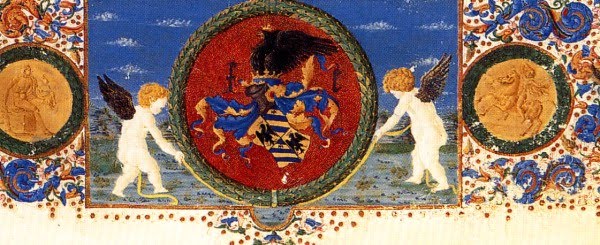

One (p. 85) is Leonardo Bellini, Venice 1462. According to Giordiana Mariani Canova, author of the commentary on this miniature. the borders of this work for the newly elected Doge (of the Moro family whose coat of arms we see) resemble those of a Virgil illuminated in 1458 by the Ferrarese miniaturist Georgio d'Alemagna (another German for you to track down, Huck?). The Virgil had been done for a Venetian diplomat for whom Leonardo is known to have done a Lactantius in 1457. The animals around the putti supposedly represent virtues or vices. I have not found any reproductions from the Virgil

The other two miniaturists whose putti have middle-aged faces are the two main collaborators on the Borso d'Este Bible (Ferrara 1455-1461), Taddeo Crivelli and Franco de' Russi. Crivelli has one such putto in the detail from the Borso Bible that I posted earlier, viewtopic.php?f=12&t=463&start=30#p6144; it also has the similar trees. He also has similar putti elsewhere in the Borso Bible, most strikingly in his depiction of Cain.

Some putti in the margins are similar as well (below left), and also some in a book of hours, late 1460's (below right), as documented in The Gualenghi-d'Este Hours, by Kurt Barstow (where I also get the black and white Borso Bible illuminations). It is known that Crivelli was in Bologna in the 1470's and may have learned engraving.

De' Russi's odd, middle-aged putti are from his time in Padua, where he moved in the 1460's, doing illuminations of manuscripts (pp. 83, 218) according to Canova (Painted Page p. 218). The putti below are from 1463 (only the left one, of course) and 1465-1470. The first is for an Oratio Gratulatorio composed by Bernardo Bembo, then a student at Padua and later to become a great humanist and politician. Yhe occasion was the election of Cristoforo Moro as Doge of Venice. His coat of arms, which we saw in the Bellini, is on the page below the inscription, of which I reproduce only a part. The other illumination, Canova tells us, was probably for an academic at the same University, whom we see sitting in the chariot being pulled by Minerva's owls.

De' Russi's trees, like Crivelli's, are similar to those of the "Mantegna." I posted an example earlier (viewtopic.php?f=12&t=463&start=30#p6149), from illuminations he did for a book printed in 1470 Venice by Vindelinus de Spira. His putti in that work don't look so odd, as you can see in that post.

According to Painted Page, illuminators in Northern Italy, unlike those of Florence, frequently changed cities. I have found no evidence that any besides Crivelli did engraving. But considering that Crivelli probably did, perhaps de' Russi did, too. The skills are somewhat transferable, as both media use pens.

So far it is still hard to place the engraver. If he is the same as the engraver of the one of putti in a vineyard, then his trees are like those of Florentines and his putti. His putti are like those of one Florentine engraving but also from more northern cities, Bologna north and east, who also have the trees.

The other engraving that Levenson et al and Zucker attribute to the same hand as the grape-harvest, is the Death of Orpheus, E.3.17 in Hind, which I showed earlier. .

Levenson

compares the two Maenads to the "Mantegna's" Luna and Calliope. He

doesn't say why, but the main reason, it seems to me, is that the lines

of the Maenads' robes and those of the two "Mantegna" figures similarly

suggest motion, whereas with most other "Mantegna" figures the lines

suggest repose.

It is not at all obvious to me why the engraving should be Ferrarese, except for the similarity to the "Mantegna" and the two standing Belfiore Muses. The rocks and hills are found in Florentine art of the period as well. Why not a Florentine engraver using Ferrarese design elements? The Belfiore Muses are notable for their repose; using the lines of robes to connote motion is a Florentine characteristic, as for example in Bozzoni's famous "Dance of Salome" (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: ... 461-62.jpg). And precipices were a standard feature of Florentine engravings in the 1460's, considerably before they appeared in Ferrara's Schifanoia. There are some in Baldini's pre-1465 "Planets" and "Triumphs" series, for example.

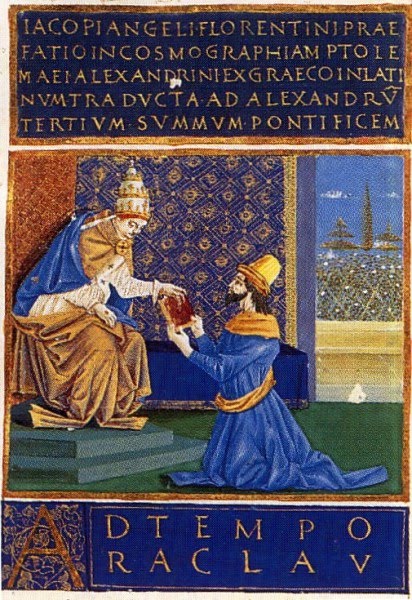

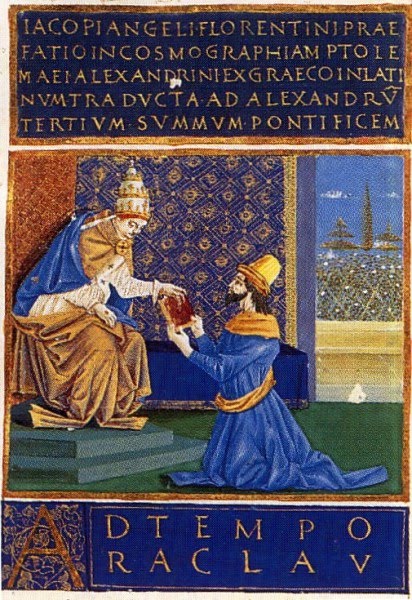

Who could have done the engraving? I found just one miniaturist who depicts vegetation in the style of the grape-harvest and "Mantegna" engravings. The illumination is of a 1472 Florentine Ptolemy Cosmographia. You can see the whole page and the other frontispiece to the same work at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Cosmographia_ms._Urb._lat._277.The attribution is to Francesco Rosselli. Rosselli was a famous Florentine engraver and cartographer. The attribution of the illumination to him is not secure, but it is the one most favored. The scribe is known to have been Ugo or Hugo de Comminellis, a Frenchman living in Florence (Suzanne Boorsch, “The case for Francesco Rosselli as the Engraver of Berlinghieri’s Geographia, Imago Mundi Vol 56 Part 2, 2004, p. 163, Albina de la Mare, "Messer Piero Strozzi," in Calligraphy and Palaeography: Essays presented to Alfred Fairbank, ed. A. S. Osley, p. 65).

Here are some details of Rosselli illuminations that are strikingly like those of the "Mantegna." I get them from a reproduction in the book Gutenberg e Roma: Le origin della stampa nella citta dei papi 1467-1477. First, for trees:

And for the little vegetation on the ground:

It is not at all obvious to me why the engraving should be Ferrarese, except for the similarity to the "Mantegna" and the two standing Belfiore Muses. The rocks and hills are found in Florentine art of the period as well. Why not a Florentine engraver using Ferrarese design elements? The Belfiore Muses are notable for their repose; using the lines of robes to connote motion is a Florentine characteristic, as for example in Bozzoni's famous "Dance of Salome" (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: ... 461-62.jpg). And precipices were a standard feature of Florentine engravings in the 1460's, considerably before they appeared in Ferrara's Schifanoia. There are some in Baldini's pre-1465 "Planets" and "Triumphs" series, for example.

Who could have done the engraving? I found just one miniaturist who depicts vegetation in the style of the grape-harvest and "Mantegna" engravings. The illumination is of a 1472 Florentine Ptolemy Cosmographia. You can see the whole page and the other frontispiece to the same work at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Cosmographia_ms._Urb._lat._277.The attribution is to Francesco Rosselli. Rosselli was a famous Florentine engraver and cartographer. The attribution of the illumination to him is not secure, but it is the one most favored. The scribe is known to have been Ugo or Hugo de Comminellis, a Frenchman living in Florence (Suzanne Boorsch, “The case for Francesco Rosselli as the Engraver of Berlinghieri’s Geographia, Imago Mundi Vol 56 Part 2, 2004, p. 163, Albina de la Mare, "Messer Piero Strozzi," in Calligraphy and Palaeography: Essays presented to Alfred Fairbank, ed. A. S. Osley, p. 65).

Here are some details of Rosselli illuminations that are strikingly like those of the "Mantegna." I get them from a reproduction in the book Gutenberg e Roma: Le origin della stampa nella citta dei papi 1467-1477. First, for trees:

And for the little vegetation on the ground:

A muzzled dog and deer appear also in another illumination attributed to Rosselli, #48 in The Painted Page,

ed. Alexander, c. 1470-1480. The attributed scribe, "Hubertus," was

active in Florence "from at least 1462 to the mid-1470's," according to

Alexander.

In the 1472 illumination, the face and headgear of the Pope are similar to that in the "Mantegna," and in the 1467 Bologna illumination that I posted (from Trionfi.com) at the beginning of this thread (relevant detail second below).

There are putti, too, although not middle-aged.

However the lettering is similar to that of the "Mantegna."

In the 1472 illumination, the face and headgear of the Pope are similar to that in the "Mantegna," and in the 1467 Bologna illumination that I posted (from Trionfi.com) at the beginning of this thread (relevant detail second below).

There are putti, too, although not middle-aged.

However the lettering is similar to that of the "Mantegna."

This

lettering was presumably done by de Comminellis. He did two other

Ptolemies and part of a third, which was finished by the Florentine

Messer Piero Strozzi (Albina de la Mare, "Messer Piero Strozzi," in Calligraphy and Palaeography: Essays presented to Alfred Fairbank,

ed. by A. S. Osley, p. 65). In an earlier post I noted the similarity

of some of Strozzi's other lettering to that of the "Mantegna." De la

Mare relates that Strozzi's father Benedetto took up copying

manuscripts to supplement his income after the Medici put punitive

taxes on all the Strozzi; the son, rector of a church on the outskirts

of Florence, followed in the father's footsteps.

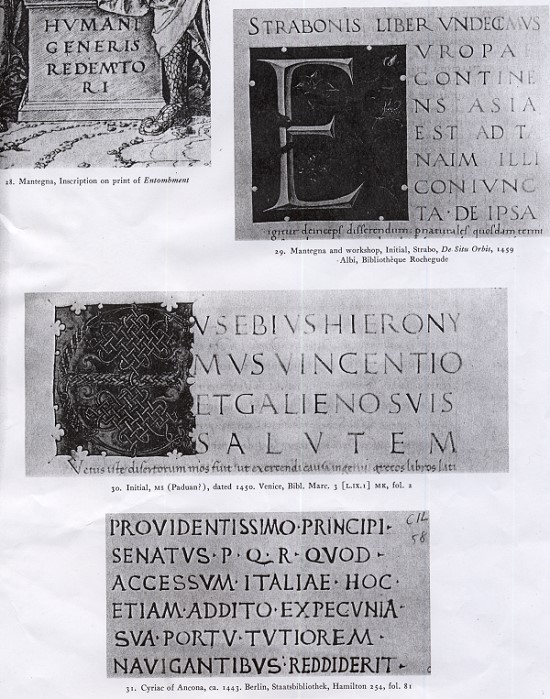

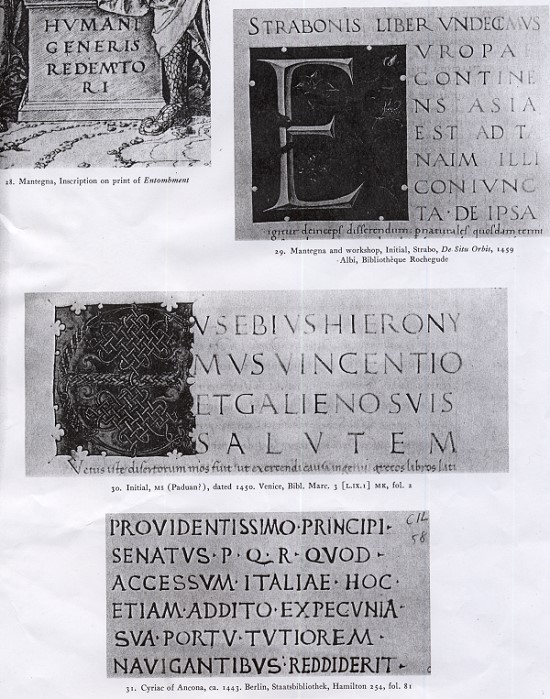

Here you will notice how the letterer does his "M's": sometimes with diagonal sides, sometimes with vertical ones, just as in the Mantegna. The middle of the M often does not reach the baseline. The "M's" in the "Mantegna" have a similar variability. However in general the lettering is no different from that in illuminations by other Italian artists and scribes in Florence and other Italian cities: e.g. Rome (including the 1478 Rome Ptolemy), Mantua, and Venice. Here are some examples to give you an idea of the style (from Millard Meiss, "Toward a More Comprehensive Renaissance Paleography," Art Bulletin June 1960):

One factor in Rosselli's favor is the inventory of his shop after his son's death in 1525. Besides many of the engravings commonly attributed to him, including maps as well as series of Prophets, Sibyls, and Triumphs (Boorsch p. 157), it listed such games as "Game of the Seven Virtues," "Game of the Planets," and "Game of the Triumphs of Petrarch" (Hind p. 222). There is no listing corresponding to the 50 Mantegna cards specifically, however.

Another factor is that Rosselli seems to have traveled a lot. In 1470 he reportedly was in Siena, doing illuminations and in 1480 he went to Hungary for 2 years (Hind 1938, p. 10). He ended his career in Venice. So why not, at the start of his career, also Bologna and Ferrara, to see the works of the artists there? He reportedly didn't marry until the 1470's (Boorsch p. 155).

Admittedly, many of the engravings now attributed to Rosselli do not look like those of the "Mantegna." But Levenson, in his discussion of Rosselli, distinguishes three different styles, at different periods. Here are two of them, early and middle:

The earliest style, in the mode of its lines and shading, is not dissimilar from the "Mantegna" series. That it is the earliest style is indicated by whom some of these engravings copy: their composition resembles the earlier Florentine niello master Finiguerra.

Rosselli typically copied others' designs. Early on, his model was Finiguerra. Then it was Baldini, and later on Botticelli. Boorsch thinks that his older brother Cosimo Rosselli, a painter well-regarded enough to have been included as one of the painters of the Sistine Chapel, did many of his designs, as similar figures can be spotted on the Chapel's walls (p. 153).

As a cartographer, Rosselli's only signed and dated set of maps was in 1506 Venice. But there were 20 copper plates of maps in an inventory of Rosselli’s shop after his son’s death in 1525 (Boorsch p. 157). Boorsch thinks that Rosselli engraved the 1482 Geographia of Berlingieri, before he left for Hungary. (There is consensus that the maps were done before the poem was.) As she demonstrates, the heads representing the winds there are quite similar to representations of winds in his 1506 map. The following is from her article, p. 163:

Here you will notice how the letterer does his "M's": sometimes with diagonal sides, sometimes with vertical ones, just as in the Mantegna. The middle of the M often does not reach the baseline. The "M's" in the "Mantegna" have a similar variability. However in general the lettering is no different from that in illuminations by other Italian artists and scribes in Florence and other Italian cities: e.g. Rome (including the 1478 Rome Ptolemy), Mantua, and Venice. Here are some examples to give you an idea of the style (from Millard Meiss, "Toward a More Comprehensive Renaissance Paleography," Art Bulletin June 1960):

One factor in Rosselli's favor is the inventory of his shop after his son's death in 1525. Besides many of the engravings commonly attributed to him, including maps as well as series of Prophets, Sibyls, and Triumphs (Boorsch p. 157), it listed such games as "Game of the Seven Virtues," "Game of the Planets," and "Game of the Triumphs of Petrarch" (Hind p. 222). There is no listing corresponding to the 50 Mantegna cards specifically, however.

Another factor is that Rosselli seems to have traveled a lot. In 1470 he reportedly was in Siena, doing illuminations and in 1480 he went to Hungary for 2 years (Hind 1938, p. 10). He ended his career in Venice. So why not, at the start of his career, also Bologna and Ferrara, to see the works of the artists there? He reportedly didn't marry until the 1470's (Boorsch p. 155).

Admittedly, many of the engravings now attributed to Rosselli do not look like those of the "Mantegna." But Levenson, in his discussion of Rosselli, distinguishes three different styles, at different periods. Here are two of them, early and middle:

The earliest style, in the mode of its lines and shading, is not dissimilar from the "Mantegna" series. That it is the earliest style is indicated by whom some of these engravings copy: their composition resembles the earlier Florentine niello master Finiguerra.

Rosselli typically copied others' designs. Early on, his model was Finiguerra. Then it was Baldini, and later on Botticelli. Boorsch thinks that his older brother Cosimo Rosselli, a painter well-regarded enough to have been included as one of the painters of the Sistine Chapel, did many of his designs, as similar figures can be spotted on the Chapel's walls (p. 153).

As a cartographer, Rosselli's only signed and dated set of maps was in 1506 Venice. But there were 20 copper plates of maps in an inventory of Rosselli’s shop after his son’s death in 1525 (Boorsch p. 157). Boorsch thinks that Rosselli engraved the 1482 Geographia of Berlingieri, before he left for Hungary. (There is consensus that the maps were done before the poem was.) As she demonstrates, the heads representing the winds there are quite similar to representations of winds in his 1506 map. The following is from her article, p. 163:

I would add that the Berlinghieri wind-heads are even more similar to those in Rosselli's

earliest known work (1465-1470 according to Levenson), the Deluge,

modeled on a drawing by Finiguerra. From this upper-left corner of the

engraving, I include more details so that you can compare it to the

"Mantegna" engravings (e.g. the cross-hatching in the Artisan), which

must have been done around the same time or a little later.

On three of the Berlinghieri regional maps, moreover, the mountains are similar to those of the 1478 Ptolemy (but with shading on their left instead of their right sides). It is these 1478 mountains, you will recall, that Hind found similar to those in the "Mantegna."

The seas are also represented similarly, with masses of little horizontal lines.

But on all the other maps in the Berlinghieri series, the mountains are done quite differently; they are masses of little diagonal lines surrounded by a double line partly empty and partly filled.

I suspect that more than one engraver was at work. Rosselli would have done the wind-heads and the maps with one of the two styles of mountains. If he also worked on the 1478 Rome around the same time, perhaps he only had time for the three maps.

Such wind-heads also resemble the middle-aged putti in the grape-harvest engravings. Here are two more from the Berlinghieri world map:

Another example of middle-aged faces on putti is this Baldini engraving for the 1481 edition of Dante's Inferno, printed by the same printer as did the Berlinghieri maps.

On three of the Berlinghieri regional maps, moreover, the mountains are similar to those of the 1478 Ptolemy (but with shading on their left instead of their right sides). It is these 1478 mountains, you will recall, that Hind found similar to those in the "Mantegna."

The seas are also represented similarly, with masses of little horizontal lines.

But on all the other maps in the Berlinghieri series, the mountains are done quite differently; they are masses of little diagonal lines surrounded by a double line partly empty and partly filled.

I suspect that more than one engraver was at work. Rosselli would have done the wind-heads and the maps with one of the two styles of mountains. If he also worked on the 1478 Rome around the same time, perhaps he only had time for the three maps.

Such wind-heads also resemble the middle-aged putti in the grape-harvest engravings. Here are two more from the Berlinghieri world map:

Another example of middle-aged faces on putti is this Baldini engraving for the 1481 edition of Dante's Inferno, printed by the same printer as did the Berlinghieri maps.

One final connection is that the same scribe who lettered the 1472 Ptolemy that Rosselli illuminated also lettered the manuscript copy that Berlinghieri had intended to send to the Duke of Urbino (Boorsch p. 163).

But there are some problems about attributing the "Montegna" to Rosselli. One is Hind's point that Florentine engravings have a cloudiness that the "Mantegna" and the other engravings attributed to that master lack. However this cannot be said for all Florentine engravings. It may depend on how many impressions were made before the one we know. Also, it is possible that the cloudiness is part of the printing process, and the printer in Northern Italy for some reason (say, the influence of a German engraver who had moved south) had a different technique. Nielo engravings, which appeared first in Italy, almost always have a cloudiness; perhaps it took the Florentines a while to wean themselves from that look.

Another problem with Rosselli is his age and experience. Levenson says of his early prints, "The fact that some were based on drawings provided by Maso Finiguerra, who died in 1464, makes one wonder whether Rosselli could not have begun engraving shortly before Maso's death" (p. 59). Then the "Deluge' might be as early as 1465, as he suggests. Could someone so young (about age 16 in 1464) and inexperienced have done the "Mantegna," which I and most art historians date to 1464-1467? I do not know the answer. Rosselli proved to be both very talented and very prolific. If he was only copying others' designs, I don't see why not. (I can't imagine that they were done later, because we know that some of the "stations of life" were done by 1467 and at least four of the virtues by 1468.) Alternatively, perhaps there was another young engraver-illuminator, slightly older and more experienced but with the same background, who did the 1472 and other illuminations attributed to Rosselli and also the engravings identified by Levenson. Boorsch thinks that all the attributions of manuscripts and paintings to Rosselli "should be carefully re-examined" (p. 153). But whoever he was, he must have Florentine connections, because the scribe was based in Florence.

I conclude that the engravings of the "Mantegna" have a Ferrarese inspiration, butcould easily have a Florence-trained engraver, coming out of the workshop of Finiguerra after the master's death. The same engraver, or another member of the same workshop, may have engraved the 1478 Rome Ptolemy, and parts of the the 1482 Berlinghieri Geographia in Florence.

But there are some problems about attributing the "Montegna" to Rosselli. One is Hind's point that Florentine engravings have a cloudiness that the "Mantegna" and the other engravings attributed to that master lack. However this cannot be said for all Florentine engravings. It may depend on how many impressions were made before the one we know. Also, it is possible that the cloudiness is part of the printing process, and the printer in Northern Italy for some reason (say, the influence of a German engraver who had moved south) had a different technique. Nielo engravings, which appeared first in Italy, almost always have a cloudiness; perhaps it took the Florentines a while to wean themselves from that look.

Another problem with Rosselli is his age and experience. Levenson says of his early prints, "The fact that some were based on drawings provided by Maso Finiguerra, who died in 1464, makes one wonder whether Rosselli could not have begun engraving shortly before Maso's death" (p. 59). Then the "Deluge' might be as early as 1465, as he suggests. Could someone so young (about age 16 in 1464) and inexperienced have done the "Mantegna," which I and most art historians date to 1464-1467? I do not know the answer. Rosselli proved to be both very talented and very prolific. If he was only copying others' designs, I don't see why not. (I can't imagine that they were done later, because we know that some of the "stations of life" were done by 1467 and at least four of the virtues by 1468.) Alternatively, perhaps there was another young engraver-illuminator, slightly older and more experienced but with the same background, who did the 1472 and other illuminations attributed to Rosselli and also the engravings identified by Levenson. Boorsch thinks that all the attributions of manuscripts and paintings to Rosselli "should be carefully re-examined" (p. 153). But whoever he was, he must have Florentine connections, because the scribe was based in Florence.

I conclude that the engravings of the "Mantegna" have a Ferrarese inspiration, butcould easily have a Florence-trained engraver, coming out of the workshop of Finiguerra after the master's death. The same engraver, or another member of the same workshop, may have engraved the 1478 Rome Ptolemy, and parts of the the 1482 Berlinghieri Geographia in Florence.

Alternatively,

to be sure, there were engravers in the north. Mantegna had a school

that turned out engravings. It is not clear that more than a few of the

engravings commonly attributed to him were done by the master himself.

And lettering was a Venetian speciealty.

THE “MANTEGNA”: CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER SPECULATIONS

I agree with the art historians that the engravings were initially done in the 1460's; around 1465. Some or all were lacking backgrounds and various attributes such as animals. They may have lacked letttering. When these were added is unclear, including whether they were before or after the work on the Schifanoia; certainly, juding from the watermarks, by 1473, and all in Northern Italy, for the Venetian market.They may even have been printed in Venice, which was more advanced in that area than Bologna.

The engravings are based on designs from the 1450's, closer to the beginning or middle of the decade than the end, and more likely in Bologna than Ferrara. For Bologna, I offer (a) Galasso's move there, as the most likely candidate for the "anonymous Ferrarese" whose style is closest to the cards; (b) the marked divergence of the "Mantegna" from Borso's (as opposed to Leonello's) Belfiore Muses and the dominant images of the Schifnoia, i.e. the decans; (c) the presence there of the 1467 miniature, (d) the keys of the Pope card as Nicholas V's device, and possibly (e) the resemblance in engraving technique to Florentine engravings of the time and (f) the later presence there of the Belfiore Euterpe and Melpemone. Moreover (g), Bologna, with its internecine feuds, suffered from much passion and intensity; the elevated but conventional mood of the cards, in contrast to the best of Ferrarese art, would have been welcome there. For the designs, in favor of the 1450s we have the 3 Belfiore Muses, Galasso's move, possible reference to Nicholas V in the Pope card, and facial features in that card similar to the Popes of the 1450s and lack of resemblance to Paul II.In favor of the early 1460s isthe resemblance to the drawings of Marco Zoppo.

Why were the cards made? They are visual representations of the "great chain of being," from the lowest representative of humanity to God himself. They are humanist propaganda for the adoption of the Greco-Roman tradition by artists, writers, and the educated public, and they are Christian propaganda for their subservience to Christianity. They are a defense of the power of the established social order, the Virtues, the Liberal Arts, the Muses, and the Greco-Roman myths to elevate humanity step by step to an appreciation of the divine. They might also have been an instructional card game with five suits. But if so, the instruction about many of the Muses and a few of the Liberal Arts is not very good, as many are not very differentiated from one another; the classical sources provided them with much more distinctive visual attributes.

Perhaps the cards were made in connection with specific celebrations, and in something of a hurry (which would explain the repetitive nature of the Muses). If occasions in Bologna are desired, the wedding of Sante Bentivoglio and Ginevra Sforza in 1454 comes to mind for the hand-made version, and that of Giovanni II Bentivoglio and Ginevra Sforza in 1464 (Ady p. 139) for the engravings. Ginevra seems to have had a special interest in the printing industry (Ady p. 162).

If Bessarion was a force behind the project, they could have been made almost anywhere, although still from designs made in Bologna. Bessarion was based in Rome but attended the Congress of Mantua in 1459, visiting Bologna both before and after. The old story (in Seznec, p. 138f, and Brockhaus, posted by Trionfi) about Pius II, Cusa and Bessarion devising the game at Mantua could have a sliver of truth: not a game, and not Cusa or Pius, just Bessarion. Bessarion, who later, according to Wikipedia, founded the Petrarch library, was very much present at the Congress, and so were delegates from everywhere, any of whom could have participated in the project.

Even Mantegna, by then resident in Mantua, could have been involved. Vasari, to be sure, spoke of Mantegna's engraved "triumphs," but one must be careful not to take him out of context. As Ross and probably others have already pointed out, Vasari was undoubtedly referring to Mantegna's engravings of his fresco cycle, "The Triumphs of Caesar," to which Vasari previously devoted an entire long paragraph using the same words of praise. (See http://www.efn.org/~acd/vite/VasariMantegna.html.)

But according to Joscelyn Godwin (Pagan Dream of the Renaissance. p. 50, in Google Books), Giannino Giovannoni argued as late as 1981, hopefully on better grounds than some, that Mantegna designed the cards at the Congress. According to him, Mantegna designed Virtues and Muses for his tomb very similar to the cards, which were then put there by his pupils. That last is a claim that I have so far had no opportunity to verify. If one compares Mantegna's engravings in general with those of the "Mantegna," it is clear that the two artists' styles are totally different, as revealed e.g. in how the two depict the folds in fabrics: Mantegna's are complex, even busy, while those on the cards are simple, repetitive, and calm. Yet if he did identify at the end of his life with some of the designs sufficiently to want them on his tomb, perhaps he had a hand in their production or distribution, which in fact was so wide, resulting in imitation so extensive (I have not told half), that it was easy to believe that a famous artist must have done them.

At the same time, there are numerous other candidates more probable. I have mentioned Zoppo, whose drawings parallel the "Mantegna" in several cases.Crivelli and dei Russi also remain candidates; and from Florence there is Rosselli, among others less well known..

If dei Russi did the designs, it would have been while he was working for Venetian patrons, i.e. during his time in Padua, 1462-1471, and definitely before he moved to Urbino, c. 1474 (Alexander, ed., The Painted Page, entries for dei Rossi). Dei Russi, it turns out, was probably in Bologna 1452-1455, moving there the same time Galasso did, working for Bassarion, illuminating a choir book series; he continued to work on this project in Ferrara at the same time as he was doing the Borso Bible, 1456-1561 (Pia Palladino, Treasures of a Lost Art, p. 78).

If Crivelli was the designer, it would have been at some time when he was not deeply involved in a book illumination. He is known to have finished one series in 1465, another in 1467, another c. 1469, another in 1470. and another in about 1469 or 1470 (Kurt Barstow, The Gualengi-d'Este Hours, p. 32). When did he have time to design the "Mantegna"? It may be significant that of the small number of saints for which the 1469-1470 Gualengi-d'Este Hours has illuminations, two (both done by a different illuminator, Guglielmo Giraldi) were from Bologna: Catherine of Bologna (who wasn't canonized until the 18th century) and the exceedingly obscure and unofficial St. Ossanus. Also, in Bologna Crivelli's first recorded work was for the Benedictines of San Procolo "working on initials for choir books" (Barstow p. 32). He pawned the parchment, and it was retrieved by the monks! The significance is that in 1468 engravings of four of the Virtues from the "Mantegna" showed up pasted into a manuscript now held by the Benedictine monastery in St. Gallen, Switzerland. Crivelli's misadventure at least shows that there was an active Benedictine manuscript-making industry in Bologna then.

But there were many Ferrarese-trained illuminators at that time, as Hind reminded us. I still favor Bologna as central to the "Mantegna" project. Both Crivelli and dei Russi had connections there. And that is where Florentine engravers would have primarily gone if they left Florence, because of the close political ties between the two cities.

It remains possible that the engraver also was the designer, working from sketches provided by Galasso in Bologna (as I suggested in the first section), or, less likely, by visiting Belfiore itself. And I still like to suppose Galasso himself as the designer, near the end of his own lif. his masterwork finally achieving fruition at the hand of a young man just starting out.

No comments:

Post a Comment